Sleep surgeons are always looking for ways to achieve consistent, predictable results. Our best efforts use a combination of careful patient examination, precise surgical technique, and constant reflection and experience. While we have seen major advances in surgical techniques and treatments, I would argue that we have just as much to offer in the improvements in patient examination that are available. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) was first described almost 25 years ago, but in some ways it is still in its infancy.

The VOTE Classification

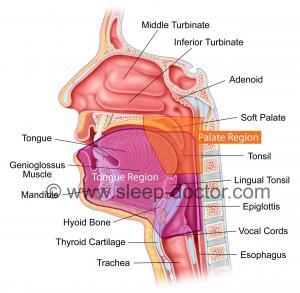

DISE is based on the idea that we want to know what structures surrounding the throat are causing the blockage in breathing that occurs in sleep apnea. Winfried Hohenhorst, Nico de Vries, and I developed the VOTE Classification in 2011 to provide a systematic approach to documenting the findings of DISE. Using the VOTE Classification, recent papers have evaluated the association between DISE findings and surgical outcomes–namely, whether DISE can predict results of sleep apnea surgery. Through the International Surgical Sleep Society, I am leading a research study that will bring together many surgeons and their patients to answer questions like this in more detail. Those of us who perform DISE often have our own sense of how important it can be for many patients, but this will be a thorough, unbiased evaluation that should have results in about a year.

The VOTE Classification summarizes a great deal of information obtained during DISE. However, an article published in the July 2015 issue of the medical journal Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery may add something else. A Chinese team characterized the extent of blockage in breathing behind the soft palate in two ways: the length of the blockage (from top to bottom) and how close it was to the back of the nasal septum. Among a group of 43 patients who underwent soft palate surgery for sleep apnea, those who responded well had a greater length of obstruction behind the soft palate (1.5+-0.5 cm vs. 1.1+-0.5 cm, p = 0.01). Those who responded well also had their obstruction behind the soft palate start farther away from the back of the nasal septum (3.7+-0.7 cm vs. 2.9+-1.0 cm, p = 0.003). Clearly, there was a great deal of overlap in the measurements between responders and nonresponders. However, there was a suggestion that there was something of a tipping point at 1.4 cm for obstruction length (lesser better) and 3.2 cm for the distance from the posterior nasal septum (greater better).

How does this match my experience with sleep apnea surgery?

In caring for my own patients, I see different lengths and location of obstruction behind the soft palate and other structures like the tongue and use this information as we discuss surgical options and the extent of sleep apnea surgery. Others have commented on this also. For example, Tucker Woodson has discussed the importance of palate shapes that somewhat combine obstruction length and location, but he and I were both impressed with the Chinese team’s work in objective measurements when we heard this presentation at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and it is great to see the article now published.

I have written previously about how DISE can change the sleep apnea surgery treatment plan. I have learned some lessons (that must be experience talking) about how I incorporate DISE when I choose procedures for many patients. This remains an exciting time in the world of sleep apnea surgery, and I look forward to sharing the latest findings with you.

− 1 = 2