Successful surgical treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea depends on accurately finding the areas in the nose and throat that are responsible for these problems, so that it is possible to select from among the many surgical options. Because patients are different, a personalized approach is required, and I have written about this in a previous blog post.

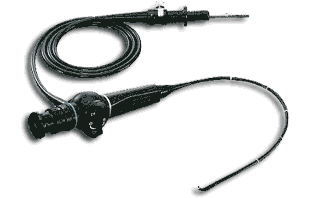

Evaluating my patients begins in the office, and one important part uses an instrument called a flexible fiberoptic endoscope (pictured below). Thin telescopes like this are used often in medicine, and otolaryngologist—head and neck surgeons (aka ENTs) use them for all types of problems because they allow us to look inside the nose and throat, examining the entire breathing passage. To find the areas most responsible for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea, I often joke with my patients that I could come to their home, place the telescope inside them, and look inside their throat while they sleep…all night long…every night for a week. Since that idea does not sound appealing for anyone, for some patients I use a technique that some colleagues and I have named drug-induced sleep endoscopy. This was developed in many centers in Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s and involves sedating patients in the operating room until they drift off to a sleep-like state, allowing me to place the telescope and look inside their throat while they start snoring and have blockage of breathing, just like they do every night at home. The idea behind drug-induced sleep endoscopy is that it can be possible to determine the factors that are most responsible for the blockage of breathing that occurs—and therefore design targeted, effective treatment.

Drug-induced sleep endoscopy for sleep apnea: more information than an X-ray

Although drug-induced sleep endoscopy has been around for over 20 years, until the last several years there were relatively few published studies. The November issue of The Laryngoscope was unique in having a group of 4 interesting papers about this technique, all led by colleagues and good friends of mine. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy can provide useful information (more on that below), but it has some drawbacks compared to something as simple as an X-ray that is simpler and cheaper. The most commonly-used X-ray for evaluation of some patients with sleep apnea is called the lateral cephalogram, an image of the head and neck performed with the patients sitting upright by some dentists, orthodontists, and oral surgeons. The first study was from our group at UCSF and involved my own patients. Dr. Jonathan George led this study comparing the findings of drug-induced sleep endoscopy and lateral cephalogram. Based on a detailed analysis of the lateral cephalogram, conducted by orthodontist colleagues at the UCSF School of Dentistry, the study showed that the findings of the two evaluations were different, suggesting that the cheaper and simpler X-ray could not replace the need for drug-induced sleep endoscopy.

Measuring the degree of airway blockage in sleep apnea with more detail

Drs. Erica Thaler and Richard Schwab from the University of Pennsylvania led another study, which used sophisticated imaging software to quantify the extent of blockage of breathing that occurred during drug-induced sleep endoscopy. Previous authors, myself included, have generally used qualitative judgment (“eyeballed”) the degree of blockage of breathing that occurs when various structures surrounding the throat collapse, whether the soft palate (roof of the mouth), oropharyngeal lateral walls (sides of the throat), tongue, or epiglottis (trap door that protects the windpipe when you swallow so that food and liquids do not “go down the wrong way”). This study showed not only that blockage in multiple areas of the throat is common—which has been shown in previous studies, including our own, and explains why single procedures often do not work well for patients with sleep apnea—but also presented this technique for measuring the degree of blockage numerically.

Do we need to repeat drug-induced sleep endoscopy after nasal surgery?

Drug-induced sleep endoscopy is fundamentally an evaluation of the throat. Even though the nose can be very important in snoring and obstructive sleep apnea, the blockage in the nose can be evaluated when patients are awake in the office and does not change when they are sedated. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy is often performed at the time of nasal surgery, as the patients are already going to the operating room. The purpose is to have this information to plan throat surgery if the patients remain unable to tolerate positive airway pressure therapy even after nasal surgery. Dr. Mas Takashima and his group at the Baylor College of Medicine compared the findings of drug-induced sleep endoscopy in patients before and after nasal surgery, showing no significant differences and, therefore, the ability to use the trip to the operating room for these two purposes.

How does drug-induced sleep endoscopy help us predict surgical results?

Dr. Nico de Vries, from Sint Lucas Andreas Zienkenhuis in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, has performed drug-induced sleep endoscopy for over 20 years, and I have been fortunate to teach a course on the technique at the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Annual Meeting each year for the past 5 years. The key question for any surgical evaluation technique is how well it directs surgical treatment or predicts surgical outcomes. Dr. de Vries’s team showed that two drug-induced sleep endoscopy had worse outcomes after surgery. One was complete (as opposed to partial) collapse of the breathing passage due to the tongue falling back in the throat. The second was circumferential collapse behind the palate, as opposed to anteroposterior (front to back) or lateral (side-to-side) collapse. Another study from Dr. Ho-Sheng Lin and his team at Wayne State University that was published earlier this year also examined this question and showed two things: patients with obstruction due to the palate alone do well after palate surgery alone, and patients with complete collapse due to the lateral walls do not do as well after surgery that often targets the palate and tongue (but not the lateral walls).

We have come a long way in understanding the best techniques for the drug-induced sleep endoscopy examination and the information we can obtain. This is an exciting time, with innovative research adding to our knowledge base, and I look forward to continued research in the years to come.

andrew sliwkowski says:

Agree 110% – After having a lidocaine induced Endoscopy (being awake) I was able to experience what happens to me while sleeping while I was awake. After 7 sleep studies I finally had the “ah ha” moment. As you said in your article “snoring and obstructive sleep apnea depends on accurately finding the areas in the nose and throat that are responsible for these problems”. Maybe one day the use of this test could be used to titrate most effective CPAP mask/device combination. (see if the CPAP actually prevents collapsed during one’s most restorative phases) … btw. I’d like to see before and after test so that the effectiveness of the procedure and effectiveness of the treatment can be measurable most accurately.

Luigi de gregorio says:

We are starting in our Hospital (Termoli,Italy) drug induced sleep endoscopy I am an anestesiology I would appreciate very much if you can send me a protocol for sedation

greatings Luigi de Gregorio

Dr. Kezirian says:

I hope you have received my protocol and the paper on the VOTE Classification system that we wrote and is now becoming standard around the world.