Every July for the past six years, I have been fortunate to travel to Sao Paulo, Brazil, to give lectures at the International Symposium on Snoring and Sleep Apnea at the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein. The course is held at one of the top hospitals in Brazil and is organized by excellent, thoughtful surgeons: Drs. Denilson Fomin, Luci Hidal, Luis Gregorio, and Sergio Miranda. In addition to having warm and delightful people, beautiful places, and delicious food, Brazil is home to some of the leading sleep surgeons and sleep researchers in the world. These and other conferences provide the opportunity to share experiences with leaders in the field from around the world. This blog entry discusses the lateral pharyngoplasty procedure that has been developed by a Brazilian surgeon, including its most recent version that has not yet been published in the medical literature.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), treats the soft palate and is the most common sleep apnea procedure, and a previous blog post discussed its strengths and limitations. Alternative soft palate procedures, such as expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty and lateral pharyngoplasty, have been developed to improve outcomes and reduce potential side effects by focusing more on tissue repositioning rather than removal. These alternative procedures are relatively new and technically more challenging than UPPP, but I perform both because the techniques have become safe and reliable, with what I feel have been better outcomes in my patients. For both of these two procedures, modifications from the original technique have contributed to their safety and reliability, with a previous blog post describing the modifications for expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty.

Version 1 of the Lateral Pharyngoplasty Surgery for Sleep Apnea: Better Outcomes than UPPP

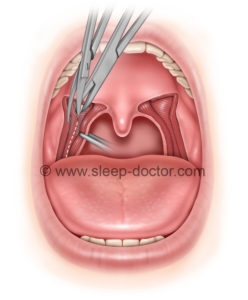

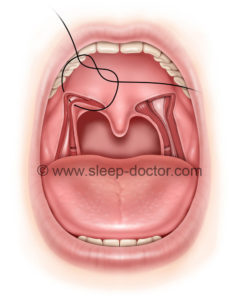

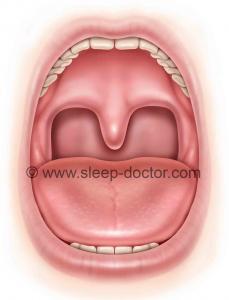

The lateral pharyngoplasty procedure was developed by Dr. Michel Cahali, an otolaryngologist—head and neck surgeon with an appointment at the University of Sao Paulo. (NOTE: I have discussed this with Cahali, including my plan to discuss his current technique on this blog.) Cahali presented the original technique in the journal Laryngoscope in 2003, based on the growing awareness in the sleep apnea world that the lateral pharyngeal walls (sides of the throat) can contribute substantially to blockage of breathing. The differences from UPPP were primarily in the focus on the lateral walls, in addition to the soft palate. After performing tonsillectomy (the lateral pharyngoplasty cannot be done in patients with previous tonsillectomy, whereas other soft palate procedures can), Cahali divided the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle that lies deep to the tonsils (towards the sides of the throat). The superior pharyngeal constrictor encircles the back and sides of the throat; it contributes to swallowing but is thickened in many patients with sleep apnea. By dividing and then repositioning this muscle, Cahali’s goal was to release the ability of this muscle to form a potential band around the throat and then sew it in a new position to make the throat wider and more resistant to collapse.

A 2004 study included 27 patients with obstructive sleep apnea, randomizing them to undergo either lateral pharyngoplasty or UPPP. There were no differences in the groups before they underwent each procedure, but the lateral pharyngoplasty group had a marked improvement in sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index decreasing from 42 to 16 events/hour, compared to the much smaller change of 35 to 30 events/hour in the UPPP group; similar differences were seen in other aspects of sleep apnea measured by sleep studies). They also performed CT scans of the neck in all patients before and after surgery; these showed greater improvement in the open area of the throat (space for breathing) in the lateral pharyngoplasty group but not the UPPP group.

Version 4 of Lateral Pharyngoplasty: Why the Changes—and What are They?

The original technique involved some careful dissection of the lateral pharyngeal walls, which is concerning given the presence of the carotid arteries in the general vicinity of this work. To avoid inadvertent injuries, the original description of the procedure involved use of an operating microscope. There were a number of challenges with the original technique: the use of the microscope, which is cumbersome and time-consuming; the dissection directly lateral through the superior pharyngeal constrictor, which places the carotid arteries at some (small) risk; and extensive suturing as part of the repositioning of tissues.

Over time, Cahali has now developed version 4 of the procedure, based on his extensive experience and implementation of a number of modifications. One major change has been the division of the superior pharyngeal constrictor in a direction along the back of the throat rather than the side of the throat, eliminating the need for the operating microscope and markedly reducing the potential for carotid artery injury along the way. In addition, there has been a change in the repositioning of tissues so that only a single, more-stable row of sutures is placed to sew the tissues in a lateral direction after the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle is divided. Many principles have not changed, including the preservation of the stylopharyngeus muscle, located just deep to the superior pharyngeal constrictor at the lowest extent of the dissection, in order to minimize the difficulties with swallowing after the procedure.

Ultimately, there is probably no single best procedure to treat the soft palate in all patients with obstructive sleep apnea, as there are patient-specific features that lead me to choose one procedure over the other in individual cases. Working together and sharing experiences with colleagues in the United States and abroad will continue to advance the field of sleep surgery, improving the matching of patients with procedures and the development of new procedures.

− 4 = 6