At the Tenth World Congress of Sleep Apnea last week in Rome, I had the opportunity to spend time with colleagues from around the world, including two groups of Italian surgeons who have developed modifications to the expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty procedure (incorporated in my explanation of the procedure on my website). This expanded on presentations from the International Surgical Sleep Society meeting in Venice earlier this year and my visit to their centers on that trip. Their modifications have led me to revisit using the expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty procedure, which I have done over the past several months.

In my last blog posting, I discussed the most common procedure performed for the treatment of sleep apnea, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), including its strengths and limitations. Although UPPP has demonstrated important benefits for many patients, it also has limitations as a single procedure to treat all patients with obstructive sleep apnea. The proportion of patients who achieve a substantial improvement of their sleep apnea after UPPP with tonsillectomy varies from 80% to 40% to 10%, depending on certain basic patient characteristics (sizes of the tonsils, tongue, and lower jaw). There are many potential reasons for these limited outcomes, including blockage of breathing in another area of the throat that is not treated with UPPP, what I call the Tongue Region. In addition, using an evaluation technique called drug-induced sleep endoscopy, one of my recent studies showed that about half of patients undergoing UPPP continue to have blockage of breathing in the Palate Region.

UPPP is no longer the only sleep apnea surgery

To improve on UPPP outcomes, alternative soft palate procedures, such as expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty and lateral pharyngoplasty, have been developed. These have both demonstrated better outcomes, compared to UPPP, in scientific evaluations of the highest quality: randomized trials where half of the patients underwent UPPP and the other half received one of these other procedures (in separate studies). Like UPPP, these procedures also involve tonsillectomy but have less tissue removal, instead focusing on tissue repositioning; the goal is to create a more open and stable space for breathing during sleep at the same time that potential side effects are reduced. Because these procedures are relatively new and technically more challenging, fewer surgeons perform them. However, I have performing both of these more often over time and have seen greater improvement in my patients.

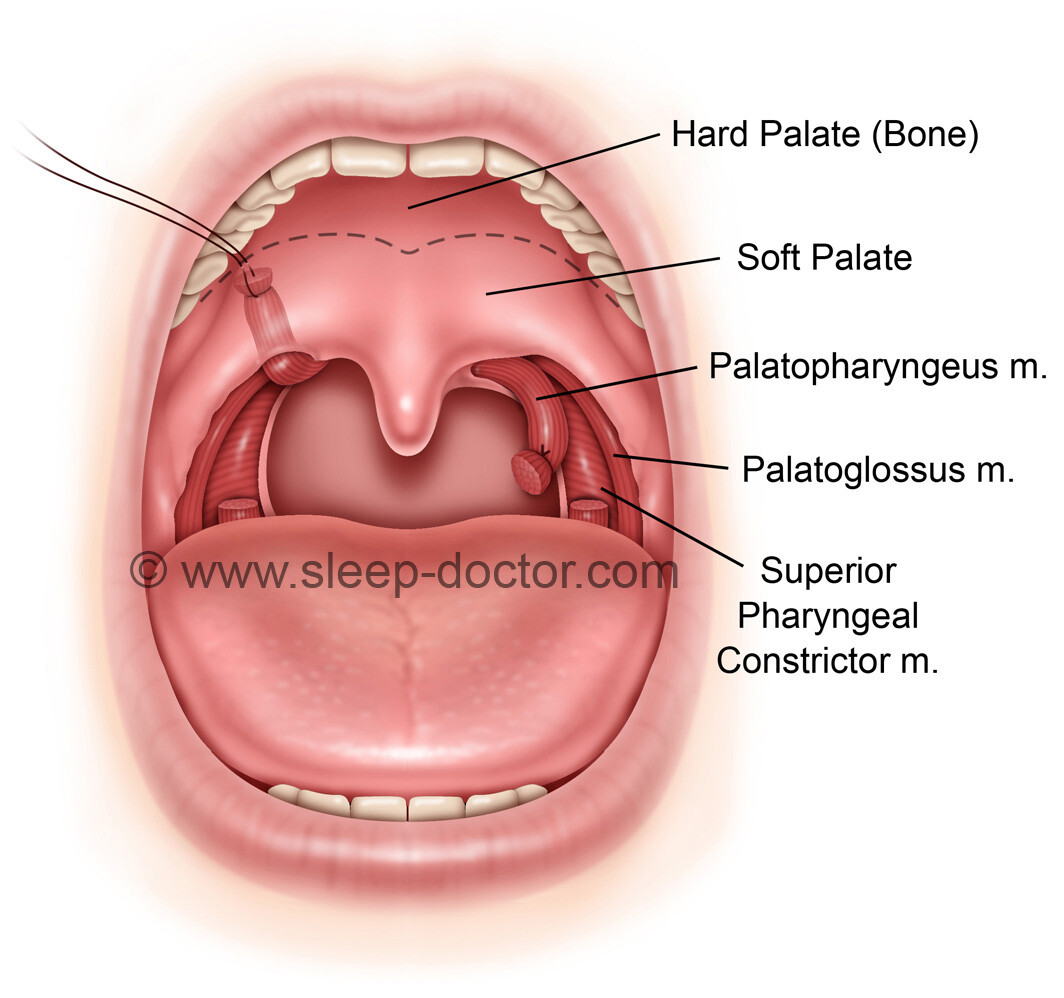

Expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty was first described by Drs. Kenny Pang from Singapore and Tucker Woodson from the United States, with a randomized trial comparing results to UPPP. After tonsillectomy, the muscle on the side of the throat behind the tonsil (called the palatopharyngeus) is separated from adjacent structures, cut near its lowest extension, freed up slightly but still kept attached to the soft palate and the sides of the throat, and then rotated anteriorly and laterally, sewing it in this new position (see illustrations below). By pulling the soft palate and other tissues at the sides of the throat forward and laterally, this opens up the space for breathing in a different way than UPPP. When people are awake, muscles are active, so it is not as important where muscles are anchored. When muscles relax during sleep, this repositioning of tissue allows the throat to remain more open because the muscles are held in a more favorable position. And the results from Pang and Woodson’s randomized trial showed that this was important; the proportion of patients responding to expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty was 78%, compared to 45% with UPPP.

The challenges of expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty surgery for sleep apnea, at least for me

The challenge with this procedure is that I, like a number of other surgeons, was having issues with these stitches holding the rotated muscle in place and securing it in a stable position. The modifications introduced by my colleagues in Italy were twofold. Instead of making a cut in the soft palate to identify a place to anchor the rotated muscle, Dr. Giovanni Sorrenti from the University of Bologna in Italy developed the first modification of creating a tunnel for this muscle to pass, without the need to cut into the soft palate, and then anchoring it in a specific way with two sutures. Dr. Aldo Campanini from Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital in Forli, Italy developed the second modification that addressed my major issue—the stitch pulling through the muscle. By tying a suture around the low end of the palatopharyngeus muscle, the sutures that hold the rotated muscle in place have something more substantial on which to hold. When I first started performing the procedure a couple of years ago, I had all 4 patients with some degree of having the sutures come loose. With these modifications, I have not had any problems (and we hope to keep it that way) and have been very happy with the results.

Dr. Sorrenti’s group, including Drs. Ignacio Fernandez and Ottavio Piccin, presented their experience with the modified expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty at the conference last week in Rome. Their results were excellent, indicating a response rate of 70%. However, the more interesting finding was their examination of factors associated with results. They showed that patients with a wider space between the anchor points for the rotated muscles (something called the inter-pterygoid distance on a CT scan) had a greater improvement in their sleep apnea, suggesting that the benefits of the procedure occur not just because of pulling the soft palate and sides of the throat forward but also pulling laterally.

Ultimately, there is probably no single best procedure to treat the soft palate in all patients with obstructive sleep apnea, as there are patient-specific features that lead me to choose one procedure over the other in individual cases. Working together and sharing experiences across national boundaries will likely play a major role in advancing the field of sleep apnea surgery, leading to improved matching of patients with procedures and the development of new procedures to treat the shortcomings of our available options.

2 + 4 =